As you will most likely be aware, an unprecedented ransomware incident took place on Friday across NHS hospitals. It is reported to have been found in around 100 countries and affected around 75,000 machines (and these figures were still increasing as we went to press.)

To help we thought we’d put together an anatomy of how it occurred, gathered from a range of different sources, to help you gain a better understanding of how it occurred and how it became so widespread so quickly.

But first, we hope that you could turn on your computer today without it being infected by malware, as many thousands across the globe won’t be so fortunate. It’s worth letting your friends and colleagues on Windows know that it’s important for their system to be fully patched with the “MS17-010” security update – https://technet.microsoft.com/en-us/library/security/ms17-010.aspx

Email awareness

It’s likely that this whole attack kick started with a spamming attack. Multiple news agencies have reported that the malware that triggers the ransomware was installed after a user opened a word document that contained macros.

For those of us involved in the cyber security space these attacks are commonplace. However, this one is unique in just how widespread it has become. The attack continued across the weekend, with Chinese state media reporting that 29,000 institutions across China having been infected by the global ransomware cyberattack. This has also continued into Monday morning with the Federal Government in Australia confirming that private businesses have been hit by the ransomware attack.

The Attachment of Doom!

So, once the email lands, and the user opens the attached documents – it’s game over!

Several things may have happened:

First, it is likely that once launched, the malware will have resent itself out to all the contacts in the users email contact list. This is one reason why the malware could travel so far, so fast.

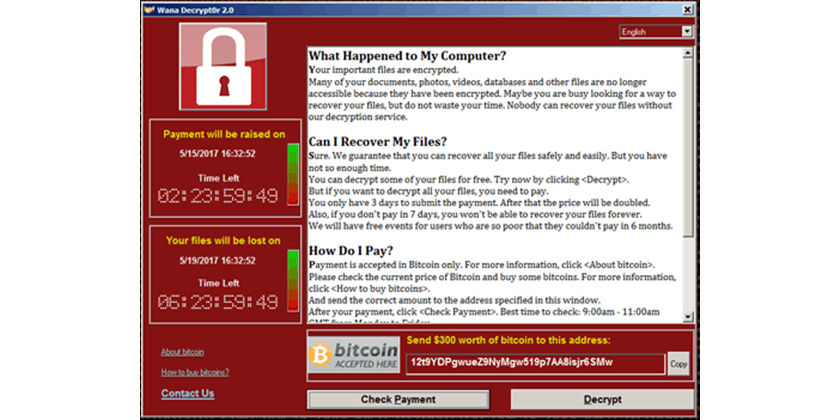

Then the Malware will have installed itself on the local machine. This would most likely have also triggered the ransomware on the local machine. This particular variant of ransomware goes by a number of names – WannaCrypt, WannaCry, WanaCrypt0r, WCrypt, WCRY. It encrypts every local file that it can and will display a screen like this:

The idea is that once the encryption takes hold the user needs to pay to gain access to their files again. The amount requested is $300. If they haven’t paid in 72 hours, the amount doubles. And if they haven’t paid inside a week, the files will all be deleted. Of course – as with all ransomware, there is no guarantee that payment will result in the decryption of files. Payment is to be made using Bitcoins – for more on this digital currency see here

EternalBlue

Don’t let the name fool you, the name EternalBlue should be striking fear into a lot of organisations right now. Sometime in the past the National Security Agency in the U.S. found a flaw in certain versions of Microsoft Windows which allowed them to access the machine remotely and install software. In a bizarre turn of events, earlier this year, the NSA themselves were hacked and the hackers found details of this flaw and a range of others. Once this became public knowledge, Microsoft released a patch for all supported versions of Windows.

However, there are several versions for which patches were not released – most notably Windows XP and Windows Server 2003. The malware that arrived last Friday was able to scan organisations network for machines which were running these unsupported versions of Windows, and then use this exploit (code named ‘EternalBlue’) to install itself across the network onto the detected machine, thus encrypting that machine.

This technique is another reason that the problem was able to spread so fast. It is also a main reason why the NHS was so hard hit. The NHS is notorious for using outdated software and operating systems – even for some of its most crucial systems.

One final thing to mention. You may have read the reports about the ‘accidental hero’ who has managed to stop any further machines becoming infected. It seems that before the ransomware takes effect and encrypts the machines, it ‘checks’ in with an internet domain. The domain is ‘www.iuqerfsodp9ifjaposdfjhgosurijfaewrwergwea.com’.

Essentially, the virus checks to see if that website is live, and if it is – the virus exits instead of infecting the machine. This seems to be a kill switch which the hackers have included to allow them to kill the ransomware campaign if they needed to. The domain above was never registered and so that website would not have been live. But one security analyst registered the domain (for a fee of £8), and this brought the website into existence and so the ransomware will no longer infect any more machines.

However, the hackers can make minor tweaks to their code and release the ransomware again without this kill switch. The effects of this could be far more devastating than what we saw on Friday.

Only time will tell if these attacks escalate, or if we’ve seen the worst of EternalBlue. However, phishing attacks will continue to occur. To avoid your company getting caught up in a global incident in the future, you may want to invest in our specialist phishing simulation software – MetaPhish that increases your employees’ sensitivity to fraudulent emails. We also have an Essential Phishing Awareness eLearning course which covers how to correctly identify a phish and what to do when you spot one.

Talk to us today for more information on how you could save your organisation from a phishing attack.